Building a macOS System Monitor with Vibe Coding and GitHub Copilot

Building software has fundamentally changed. Over the past two days, I built Peep, a native macOS system monitor application, using a development approach that would have seemed like science fiction just a few years ago. This post documents my experience combining “vibe coding” with GitHub Copilot Chat to create a production-ready Electron application with a Rust native backend.

What is Peep?

Peep is a system monitoring application for macOS that displays real-time information about your computer’s performance. Think of it as a modern, visually appealing alternative to Activity Monitor. It features:

- Real-time CPU and memory monitoring with animated gauges

- Network and disk I/O tracking with historical charts

- Process management with tree view and thread filtering

- Battery status with time remaining estimates

- Machine information including model name and macOS version

The tech stack combines Electron for the desktop shell, React and TypeScript for the UI, and Rust via Neon bindings for high-performance native system access.

Vibe Coding: A New Development Paradigm

“Vibe coding” is an emerging term for a development style where you describe what you want in natural language and iterate rapidly with AI assistance. Rather than meticulously planning every implementation detail upfront, you:

- Describe the desired outcome - “Add battery information to the header”

- Review the generated solution - AI provides working code

- Refine through conversation - “The icon isn’t showing correctly for discharging state”

- Iterate until satisfied - Continue the dialogue until it works perfectly

This approach flips traditional development on its head. Instead of spending hours reading documentation and debugging, you spend time describing and refining. The AI handles the boilerplate, the API lookups, and often catches edge cases you hadn’t considered.

The Development Journey

Starting Point: Architecture Decisions

The project began with a clear vision: a system monitor that felt native to macOS while being built with web technologies. The architecture emerged through conversation:

Me: “I want to build a system monitor for macOS using Electron”

Copilot: Suggested the full stack; Electron for the shell, React for the UI, and importantly, recommended Rust with Neon bindings for the native module rather than pure Node.js. This was crucial for performance when polling system metrics every few seconds.

The initial scaffolding; webpack config, TypeScript setup, IPC handlers, Rust/Neon integration, was generated in minutes. Tasks that would typically take half a day of configuration wrestling were done before my coffee got cold.

Copilot opens a pull request with a thorough explanation of the work that has been done. At this point I can pull the branch to my machine and do some QA.

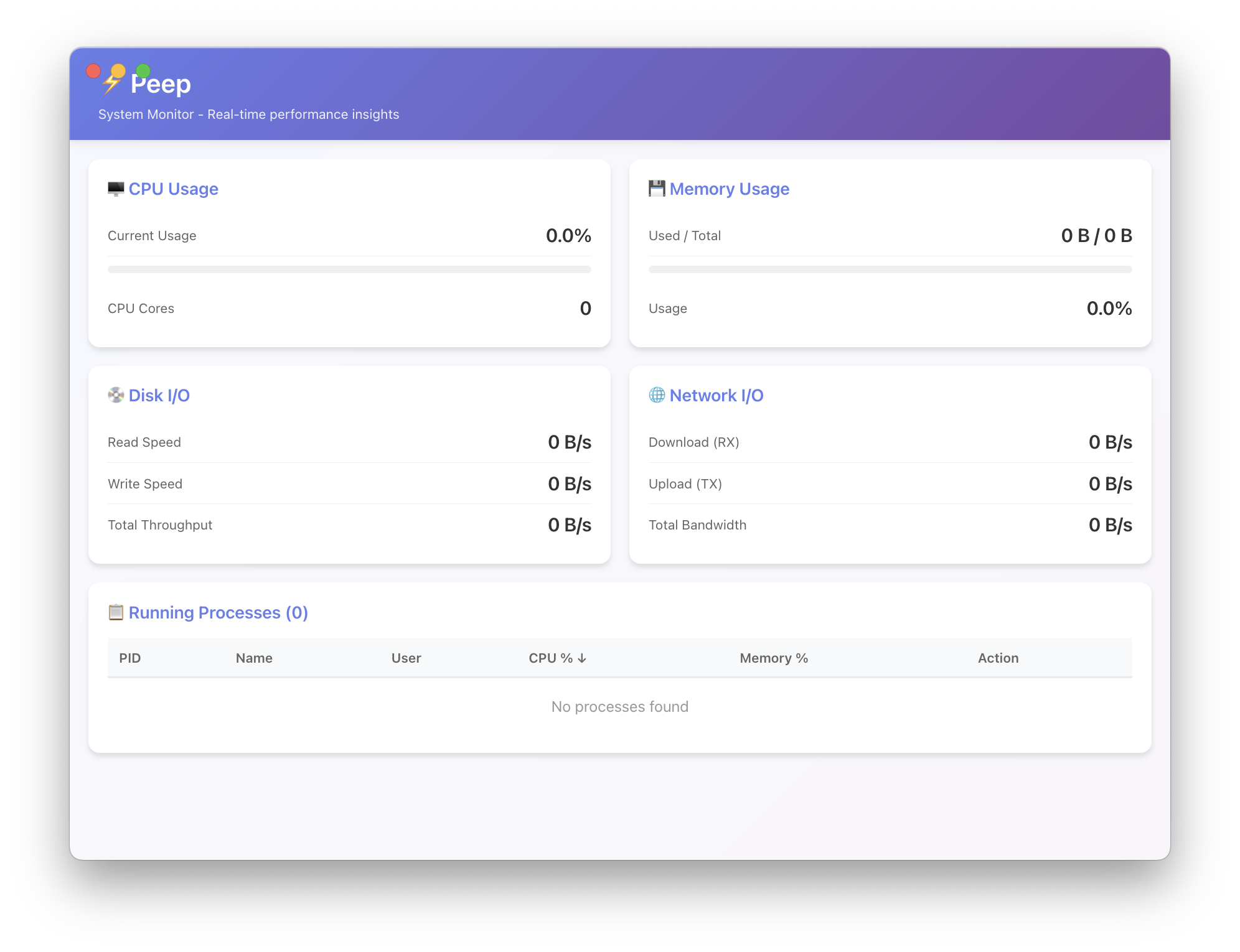

The initial version created by Copilot looked like so:

If I find any bugs or want to make some minor improvements I can add a comment to the pull request.

glenthomas commented

@copilot the nodejs project is trying to import the Rust binary and is failing with error:

Failed to load native module: Error: Cannot find module ‘../../native/index.node’

Require stack:

/Users/glen.thomas/git/peep/dist/main.js

at Module._resolveFilename (node:internal/modules/cjs/loader:1390:15)

Copilot add the eyes emoji (👀) to to my comment to acknowledge my request and gets straight to work in a new session. A new comment is added to the pull request to let me know when the next stage of the work has been completed.

Copilot AI commented

Fixed in commit e1003c2. The issue was that the native module path was using a hardcoded relative require path that didn’t resolve correctly at runtime.

Changes made:

- Updated src/main/main.ts to use path.join(__dirname, ‘..’, ‘native’, ‘index.node’) for proper path resolution

- Added @types/node and @types/electron as dev dependencies (required for TypeScript compilation)

- Updated build script to use npx cargo-cp-artifact to ensure the tool is available

- Enhanced README troubleshooting section

The native module now loads correctly. From dist/main.js, it resolves to

/native/index.node. Verified with test that shows the module loads successfully and can retrieve system info.

Feature Development: The Tree View Example

One of the more complex features was adding a process tree view that shows parent-child relationships between processes. Here’s how that conversation went:

Me: “Could we have an option to view process parent-child relationships?”

Within moments, I had:

- A

buildProcessTree()function that constructs a hierarchy from the flat process list - A

renderProcessTree()function with proper indentation and expand/collapse - Toggle buttons for switching between list and tree views

- State management for tracking expanded nodes

The implementation used the ppid (parent process ID) field that was already being collected by the Rust module. Copilot recognised the data was available and used it appropriately—something that would have required me to trace through the codebase manually.

Debugging: The Battery Icon Bug

Not everything worked perfectly on the first try, and that’s where the iterative nature of vibe coding shines. After adding battery status to the header, I noticed the icon wasn’t correct:

Me: “The battery state icon is not showing the correct icon. When the battery state is ‘discharging’, it shows the charging icon.”

Copilot identified the issue immediately: the getStateIcon() function was using includes() to match states, so “discharging” was matching the “charging” case first. The fix was simple—use exact matching with === and startsWith() instead.

This kind of bug could easily waste 20 minutes of console.log debugging. Instead, describing the symptom led directly to the fix.

The UI Polish Phase

As the core functionality stabilised, I shifted to UI refinements. This is where vibe coding particularly excels - making small adjustments is as easy as asking:

- “The columns, view type and show threads controls are stacked vertically, can they be stacked horizontally?” → Segmented button groups

- “On the CPU monitor and Memory monitor there is a bit of a vertical gap” → SVG viewport adjustments

- “Can we decrease the size of the gauges a little? Maybe 20%” → Proportional scaling of all gauge dimensions

- “The battery info is not properly centered in the header” → CSS Grid with

1fr auto 1fr

Each of these would typically involve researching CSS properties, testing various approaches, and iterating. With Copilot, I described the visual problem and received targeted solutions.

Native Integration Challenges

Some features required deeper system integration. When I asked about displaying the machine model name, the response included:

- Using

sysctlto readhw.model(e.g., “MacBookPro18,1”) - A mapping table translating hardware identifiers to friendly names

- Integration with the existing

get_os_info()Rust function

Similarly, adding the macOS marketing name (Sonoma, Sequoia, etc.) required mapping Darwin version numbers to release names—knowledge that would require research but was immediately available through Copilot.

When AI Knowledge Falls Short

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. One notable friction point came when working with the Rust sysinfo crate. Copilot confidently suggested methods and function calls that simply didn’t exist in the current version of the library.

For example, when implementing disk I/O monitoring per process, the AI suggested using methods that had either been renamed, deprecated, or never existed in the version I was using (0.37.x). The code would compile with errors like “method not found” or “no field named X on type Y”.

This is a fundamental limitation of AI coding assistants: their training data has a cutoff date, and libraries evolve. The sysinfo crate in particular has undergone significant API changes between versions, with methods being renamed and structs being reorganised.

The solution? I had to do things the old-fashioned way—pull up the sysinfo documentation on docs.rs, find the correct method names for my version, and either correct the AI’s suggestions or implement the fix myself. In some cases, I’d share the compiler error and the relevant documentation snippet, and Copilot would adjust. In others, it was faster to just fix it manually.

This experience reinforced an important lesson: AI assistants are collaborators, not oracles. They’re incredibly useful for getting 80% of the way there quickly, but you still need domain knowledge and the ability to debug when their information is stale or incorrect.

Self-Review: Getting Copilot to Improve Its Own Code

One powerful technique that addresses concerns about AI-generated code quality is using Copilot to review and improve the very code it has produced. Critics might argue that AI assistants lack sufficient context while working incrementally, potentially leading to suboptimal solutions. However, this misses a crucial capability: asking the AI to review the solution as a whole.

After Copilot had implemented the core functionality, I took a step back and asked:

Me: “Review the entire codebase and identify any issues, inefficiencies, or areas that could be improved.”

This prompted a comprehensive analysis that surfaced real problems I hadn’t noticed during rapid feature development:

🔴 High Priority Issues

- Duplicate

formatBytesfunction - Defined in 4 separate files (MemoryMonitor.tsx,DiskMonitor.tsx,NetworkMonitor.tsx,ProcessList.tsx), each with slightly different implementations - Type safety issues in App.tsx - Using

anytypes for state variables likesystemInfo,processes, andbatteryInfoinstead of proper interfaces - Preload types don’t match actual API - The

ProcessInfointerface was missing many fields the Rust module actually returns (ppid,runTime,cpuTime,status,command,diskRead,diskWrite,isThread)

🟡 Medium Priority Issues

- Native module type is

any- No TypeScript declarations for the Rust bindings - Duplicate

formatStoragefunction - Defined in bothDiskMonitor.tsxandNetworkMonitor.tsx - ChartJS registered multiple times - Each monitor component was independently registering ChartJS components, should be done once at app level

- Large inline styles in App.tsx header - The battery status section (188-275 lines) had extensive inline styles that could be extracted to CSS

- ProcessList.tsx is 664 lines - Very large component that could be split into

ProcessTable.tsx,ProcessControls.tsx, andConfirmDialog.tsx

🟢 Low Priority

- CSS variables defined but not fully used - Variables like

--spacing-xsand--font-smwere defined but many inline styles used hardcoded values - Missing React.memo on monitor components - Could prevent unnecessary re-renders on gauge/chart components

- Console.error for non-critical failures - Should use proper logging utility or remove in production

For each issue, Copilot provided context and suggested fixes. The conversation flowed naturally:

Me: “Fix the duplicate formatBytes functions”

Copilot: [Creates src/utils/formatters.ts with a single, comprehensive implementation and updates all 4 files to import it]

Me: “Add proper TypeScript types for the system info state”

Copilot: [Creates interface definitions matching the Rust module’s output and updates all any types to use them]

This self-review pattern is remarkably effective because:

- Full context awareness - During review, the AI can see all the pieces together, not just the immediate task

- Pattern recognition - It can spot anti-patterns across the codebase that emerge from incremental development

- Best practices application - It can suggest idiomatic improvements that might have been missed during rapid feature development

- Consistency checking - It identifies places where similar functionality is handled differently

The key is being explicit about the review scope. Rather than asking a vague “make it better,” specific prompts work best:

- “Review the React components for performance issues”

- “Check the Rust module for error handling problems”

- “Analyze the IPC communication for potential race conditions”

- “Review accessibility and ensure proper ARIA labels”

This approach transforms a potential weakness into a strength. Yes, AI might produce less-than-perfect code when working with limited context on individual features. But it excels at identifying those imperfections when given the full picture and asked to review holistically.

Setting Up the Release Pipeline

One area where AI assistance proved invaluable was configuring the build and release pipeline. CI/CD configuration is notoriously fiddly, with countless options and edge cases.

Me: “I would like to allow people finding this GitHub repository to be able to download and install the application. What options do I have?”

Copilot outlined several distribution strategies (GitHub Releases, Homebrew, Mac App Store) and recommended GitHub Releases with electron-builder for an open-source project. It then generated:

- A

build.ymlworkflow for CI on every push - A

release.ymlworkflow triggered by version tags - Electron-builder configuration for both Intel and Apple Silicon

- README updates with download instructions

When the workflows hit issues; wrong action names, permission errors, DMG creation failures on CI runners, each problem was solved through conversation:

- “The action

dtolnay/rust-action@stabledoes not exist” → Switched toactions-rust-lang/setup-rust-toolchain@v1 - “Package ‘electron’ is only allowed in devDependencies” → Moved the dependency

- “hdiutil detach failing on CI” → Added retry logic for flaky DMG creation

- “403 Forbidden when creating release” → Added

permissions: contents: write

Lessons Learned

When Vibe Coding Excels

- Boilerplate and configuration - Webpack configs, GitHub Actions, package.json scripts

- API integration - Knowing which Electron or React APIs to use

- Cross-referencing - Using data from one part of the app in another

- Bug diagnosis - Describing symptoms and getting targeted fixes

- Refactoring - “Can you change this from flex to grid layout?”

When to Slow Down

- Architecture decisions - Still worth thinking through yourself

- Security-sensitive code - Review carefully, don’t blindly trust

- Complex algorithms - Understand what’s generated, don’t just accept

- Performance-critical paths - Verify the approach makes sense

The Collaboration Dynamic

The most effective pattern I found was treating Copilot as a highly knowledgeable pair programmer who happens to type very fast. I would:

- Set context - Explain what exists and what I’m trying to achieve

- Ask for options - “What are the ways to do X?”

- Make decisions - Choose the approach that fits best

- Request implementation - “Let’s go with option 2”

- Iterate on details - “Can we also handle the edge case where…”

This maintains human agency over the architecture and design while leveraging AI for implementation speed.

The Results

Peep went from concept to released application in a remarkably short time. The final product includes:

- 5 monitoring components (CPU, Memory, Disk, Network, Processes)

- Native Rust module with 15+ exported functions

- Automated CI/CD with multi-architecture builds

- GitHub Releases with DMG and ZIP downloads

- Comprehensive documentation (README, CONTRIBUTING, CHANGELOG)

More importantly, the codebase is clean and maintainable. The AI-generated code follows consistent patterns, includes appropriate comments, and handles edge cases I might have missed.

Conclusion

Building Peep reinforced my belief that we’re at an inflection point in software development. The combination of vibe coding (describing intent in natural language) with tools like GitHub Copilot Chat doesn’t replace programming skill; it amplifies it.

You still need to understand what you’re building, make architectural decisions, and verify the results. But the mechanical translation of ideas into code? That’s increasingly handled by AI, freeing developers to focus on the creative and strategic aspects of software creation.

If you haven’t tried this approach, I encourage you to experiment. Start with a side project, describe what you want, and see where the conversation takes you. You might be surprised how quickly your ideas become reality.

Peep is open source and available on GitHub. Contributions welcome!

Leave a comment